Can you stay here next to me? We'll just keep drivin' Because of you I see a light The Buick's a Century, a '73 like you Some strange religion

The road between St. Louis and Nashville’s a short one, quick enough that Kevin could run sound at Sunday jazz brunch and we could make the drive when he was finished. A hot May afternoon in a house he was soon to leave, we shared a bowl before hitting the road in his little SUV, making time on the interstate for barely five hours before arriving at his old friend’s suburban Nashville townhouse.

Come on, let's go drivin'

Come on, let's take a little ride

That's the study of dyin'

How to do it right. Bring in the overnight bags, pet the dog, follow our host in search of Sunday suppertime hot chicken and fail. Nothing’s open on Sundays in the Bible belt, or the chicken’s long gone but the hot catfish remains. It stings the palette like the whiskers are still attached. No amount of sweet tea can burn it off.

It was a year and a half after the fall that destroyed my knees, and a few months after I’d finally been diagnosed with late-stage degenerative joint disease. Kevin was conscientious, getting us to the Mercy Lounge early enough to get a close parking space where we nibbled on a pot brownie before climbing the stairs to the club. Under the russet glow of Edison bulbs on the deck, we skipped the opening act, conserving what standing strength I had by sitting, passing a cannabis-loaded vape pen back and forth without drawing any unwanted attention.

The standing-room crush to the stage when Lanegan started his set included Kevin. He’d waited years to see Lanegan live, having been a child when I sat in the balcony at The Blue Note in 1993 to see him lead The Screaming Trees in Sweet Oblivion.

I wasn’t high at that show when I was 20 years old. I was sober, sitting in the balcony with my roommate, both of us learning to navigate the world of live music. I felt like I was an awkward party-crasher who would get in the way in the mosh pit and ruin everything. There was time to learn how to be a part of this world.

Except there wasn’t.

That Screaming Trees show was the night of April 5, 1993. 363 days later, Kurt Cobain of Nirvana would be dead by his own hand. When Lanegan unexpectedly died this week at the age of 57, he was the fourth of the five great vocalists of grunge to not make it into old age. Layne Staley of Alice in Chains died of a heroin overdose almost twenty years ago. We’re approaching the fifth anniversary of the night Soundgarden’s Chris Cornell died by suicide. Only Eddie Vedder, who introduced himself to my generation by growling that he was still alive, remains.

You're still alive, she said Oh, and do I deserve to be Is that the question And if so...if so...who answers...who answers...

A few years ago I spent a day making a list of musicians born in the years that put them in Generation X who had died by suicide or overdoses. Pages. The list was pages of names of the dead who were my age, killed by the contents of their minds.

It wasn’t that we lost The Voice of Our Generation™ when Kurt died in his Seattle home. It’s that he kicked open the door for the horseman who took so many of our most valuable voices and kept taking them until now my generation, small in numbers from the start, has been decimated and we’re not even retirement age yet. So many who lived have done so with broken parts, broken minds, broken hearts that never recover. At the rate we were going, working ‘73 Buick Centuries are going to soon outnumber Gen Xers.

Why? We survived lax parenting and the Cold War. Fought the forgotten wars of the 1990s in Iraq, the former Yugoslavia, Somalia along with the wars the Millenials claim as their own that were actually shared with us. We didn’t wear seatbelts or have car seats, had a tree in the parking lot of our high school where we could smoke. We suckled formula and then McNuggets. We were designed to die, and do it fast.

Along with Lanegan’s death this week, we have Russian bombs falling on Ukraine. As a kid whose hometown was namechecked as annihilated in the 1983 feel-good nuclear war romp* The Day After, I’m back to wondering what time it is on the Doomsday Clock. Not that I could run to the nearest fallout shelter with my healing new knee and the arthritic one that’s supposed to get replaced two weeks from today. I can sit here and watch bombs fall in real time on as many screens as I want with what’s left of my opioid prescription. It’s the end of the world and I feel fine.

Instead, I shift my mind to Mark, and to Kevin, and that night of standing near the stage but off to the side, a sweet spot where the bass vibrated in my sternum and the floor shimmied under my feet. I couldn’t see Mark over the heads of the crowd. It wasn’t that I was still unfamiliar with the pit, having long ago gathered my courage and tequila to join the fray, getting my feet stomped and tits groped, throwing elbows into the fleshy bellies of the kinds of boys Kathleen Hanna would send to the back of the room. I just didn’t need to be in the pit anymore. Not that this was a pit. Most of the crowd was my age, with the low end being closer to Kevin’s, about a dozen years younger than me. An excited crowd with a muted frenzy, perfect to keep at arm’s length until I realized I had no legs.

I knew I had no legs because I couldn’t feel the pain in my knees anymore, a sighing relief from thighs to floor. But I didn’t feel anything below the location of the constant muted throbs. I floated, not above the crowd or even high enough to give me a couple of inches of height to see over a few heads, but I floated, shin and calf-less, keeping myself at 5’3” where I’m used to the altitude.

Looking down, I could see my knees and my shins, covered in black leggings just as they’d been when I left home. I could see the fishbelly white skin of the tops of my feet through the cut-outs on the tops of my black Mary Janes. But I knew they were gone and I probably shouldn’t be standing. I took a seat at the bar beside a large, sweaty cooler of ice water. Yellow-bodied and red lidded just like the water coolers from my childhood softball games, I gulped one cool plastic cup of water after another, trying to wash away the cotton lining out of my mouth.

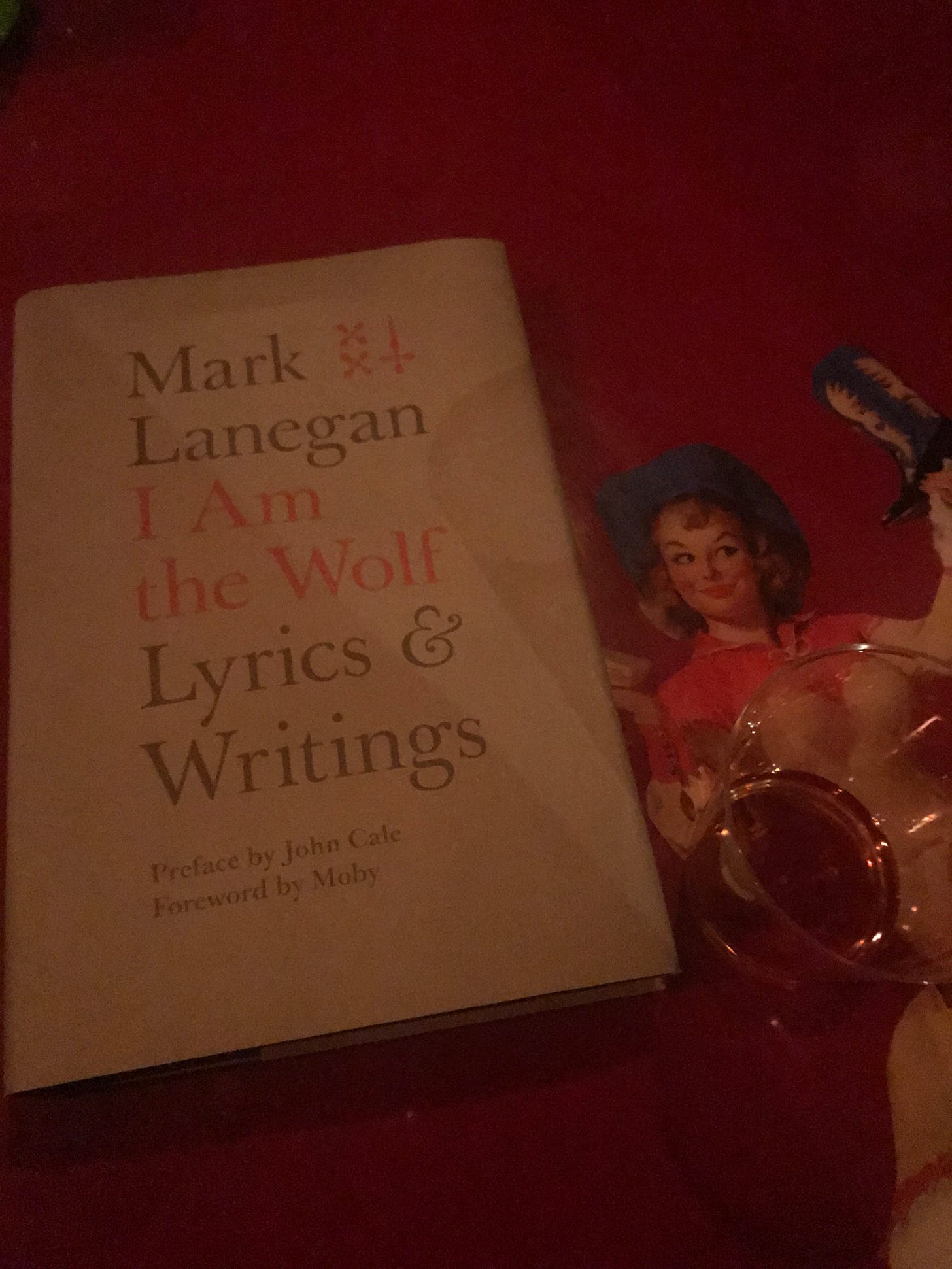

Of course, you probably know that my legs didn’t really disappear and my mouth wasn’t lined with fabric. I was simply high as absolute fuck, having forgotten that Kevin’s brownies are … potent. It made the night so foggy that I don’t recall specifics of the concert beyond that beautiful, happy feeling of the warmth of being home, where I belonged, so comfortable and content down through my soul that I laughed when a man approached me, looked at the Mark Lanegan book about his lyrics I held and asked me if I was a composer. This, in Music City and a Mark Lanegan show, with my pupils blown to the size of nickels, made me laugh so hard he left. I sipped a bourbon to see if that would bring back my missing shins.

Kevin found me at my bar perch before the show’s end, and I treated him to a Fernet and Coke. Despite being much smaller than me and having consumed roughly the same amount of brownie and vape pen, he seemed fine.

Years later, Kevin thanked me for making it possible for him to meet Mark after the show. That’s among the memories that were lost to the brownie. I have no idea how I made anything possible that night. Anything beyond the feeling of floating in the line, surrounded by the orange post-show glow, snapping photos of Kevin as he leaned across the table to talk to one of his heroes was gone. When he thanked me I scrolled through my camera roll to make sure it really happened, that I was there and we weren’t misremembering.

I remember that he had stars on his knuckles.

Afterward, Kevin and I hit a late-night bar where we drank beer and flipped through bins of records for sale before returning to our separate rooms at this friend’s house. I fell across my bed in the clothes I’d worn all day, called a friend who could barely hear my sleepy-stoned mumbles about the show, and I thought about the different pillows my head had hit so far in 2019 while traveling for concerts.

Iowa City; Chicago; Champaign, Illinois; Fulton, Missouri after my car broke down on the way to Columbia; Tulsa; Nashville. Coming up? Another trip to Tulsa, a music festival in the Berkshires, and then? I didn’t know yet. It wound up being a lot. I stayed in perpetual motion until the pandemic stopped me ten months after Nashville, giving me time to think about why I stayed on the move from city to city, going from concert to concert, alone and with friends. Because it was fun. Because I was no longer that young woman intimidated by the pit. I was a middle-aged woman who didn’t put up with the bullshit in the pit that interfered with getting lost in the music.

I’d like to think that some inkling of foresight kept me moving. I know something shifted in me when the orthopedist told me that March that my legs would never feel better than they did that day, and they felt like absolute shit that day. But I wasn’t thinking, “Go to this concert in another city because soon you won’t be able to walk and your life will never be the same” when I made my plans. Mostly because I thought I had more than two years before I’d lose my ability. It wasn’t time to start thinking about cramming in the things I might never be able to do.

But it was.

We ended our whirlwind trip with strong coffee and sweet biscuits, record stores and drum shops. Kevin always buys small instruments as souvenirs when he travels. We drove home slower than we drove to Nashville, the brownie and vape pen staying stashed, listening to Mark singing with Queens of the Stone Age:

Losin' all feelin', and I couldn't get away. Countin' and breathin', disappearing in the fade. They don't know, I never do you any good. Stoppin' and stayin', I would if I could.

Written in memory of Mark Lanegan. We’ll miss your voice and your soul. Your spirit, though, is carried by us.

*This is Gen X gallows humor, probably what keeps some of us alive. “Life’s the study of dying and how to do it right,” as Mark once sang.